The Glory

On some level, most everyone is almost always performing. Not so in the emergency department.

One of the more profound things about emergency medicine is the frequent opportunity I have to observe humanity in a very raw state.

This is true, of course, of the obvious raw physical nature of the work that I and others do in the emergency department— we see the broken bones, the vomit, the blood, pus, psychosis, nakedness, and carnage—but it’s also just as true of the raw emotional aspects of the work.

Most of my patients do not come to the emergency department for fun. It’s not an activity that is desirable or pleasurable for the vast majority of individuals in the various communities in which I’ve worked. For most of my patients, they are in my emergency department because for one reason or another, they are having one of the worst days of their lives.

I’m not much of a philosopher, but if I had to summarize my fundamental perspective of human behavior it’s that circumstances don’t cause us to be a certain way as much as they reveal us to be a certain way. I call this the “tube of toothpaste” perspective of human behavior—when life squeezes us, whatever is inside of us comes out, much like a tube of toothpaste. Pressures and stresses don’t create the toothpaste, they just make what’s already there evident for all to see.

Over the course of many years spent working in emergency departments in many geographic locations and cultures, I have had the opportunity to witness individuals react to the shock of terrible news that was completely unexpected.

“I’m sorry, but your mother has had a devastating stroke.”

“Your father is in critical condition after a massive heart attack.”

“Your daughter is in emergency surgery now due to the injuries she sustained in the car crash.”

“Your son has drowned.”

This very unique vantage point of observation working as a physician in an emergency department has taught me that often times people react very differently when they receive bad news. There are many reasons for these differing reactions. My personal opinion is that it’s a mix of culture, personality, background, and even the relationship of the individual to the patient we’re discussing. I don’t think there’s a right or wrong way to react to bad news, necessarily—people grieve in different ways—but I do believe the reaction tells us something about the individual. Matter of fact, I’m sure of it.

We live in a society that is very image conscious. Even the most free among us is still very aware of how they are perceived. Most of our behaviors are reflexively choreographed and staged in an attempt to send some sort of message to those around us. On some level, most everyone is almost always performing.

Not so in the emergency department.

In the emergency department, when unexpected tragedy befalls a person, when the waves of grief or fear wash over them, when they are struck with some sudden horrible news, the facade comes down. There is no performing in that moment. Who they truly are on the inside comes out. The toothpaste comes out of the tube.

And at no time is this more evident than when I have to give the ultimate bad news—“I’m sorry, your loved one is dead.”

These are conversations that I’ve had hundreds of times, unfortunately, over the decades I’ve practiced in the emergency department, and they are conversations to which I have not yet grown accustomed. I hope I never do. To lose the emotion, the grief, the humanity, of a moment like that would mean that I had lost some aspect of my own humanness. Walking into a room and telling a stranger that their loved one is dead—to be the person that gives them the tragic news that will upend their life—is much too personal, too intimate, too raw, to be unaffected by it. Doctors are still human beings after all.

And some of these conversations I’ve never forgotten.

When I was in residency, I had to tell an elderly couple that their adult daughter had been killed in a car wreck. The nurses had placed the couple in a private room just off of the emergency department, and with this couple was their 6-year-old granddaughter, the daughter of the deceased. When I broke the news to them that their loved one had not survived the crash, the elderly woman flung herself onto the floor sobbing and screaming, “No! It can’t be! No! No!” with the little girl wailing, “What happened? Where’s mommy? Where’s mommy? Where’s mommy? Where’s mommy?!” over and over again.

These are the sorts of experiences you don’t soon forget.

When I taught medical students at one of my prior academic positions, I used to make sure I took them with me when I had to give this sort of news. I would explain to them my own personal method for having these sorts of conversations. I would tell them specifically that nothing they say in these moments is going to make the situation better—the patient has died after all—but they can certainly make things worse by being abrasive, or dismissive, or unclear.

I would teach these students that I always start by introducing myself and then asking what the person knows about the circumstances of their loved one.

“Hi. I’m Dr. Bledsoe, the emergency medicine physician on today. What do you know about what happened?”

Sometimes the people knew a great deal about the circumstances of their loved ones, but just as often they would know next to nothing. Whatever their answer, I’d pick up the narrative where they’d left off, explain the attempts to resuscitate, and then very clearly say that their loved one had died.

Often in these circumstances, euphemisms are not enough. It’s not enough to say “passed away” or “not coming back” or “the resuscitation was not successful.” The shock of the moment is such that unless you say “dead” or “died” there is often some level of cognitive dissonance, some lack of recognition. Saying “dead” may seem overly blunt, but in many cases it’s a required, and actually benevolent, point of clarity.

The conversations often would go something like this:

“So after you found your father unresponsive on the floor and called 911, the paramedics arrived and began the resuscitation. They told us that when they got to your father, he wasn’t breathing and his heart was stopped. The paramedics initiated all the proper resuscitative measures, and worked on your father the entire trip to the hospital, but when he arrived to the emergency department his heart was still not beating. We continued to work on him for several minutes and did everything we could possibly do, but I’m sorry, your father did not make it. He has died.”

These moments can be very difficult. Walking into a room filled with people who are anxious for good news, longing for good news, looking at you while hoping and praying that their loved one has somehow miraculously survived. You can feel the expectation. Then telling them the worst news possible, well, this is not an easy thing. Most decent people have an innate urge to comfort or encourage the hurting. But you can’t give false hope or leave any doubt. You enter the room knowing that no matter how professional your delivery or kind your tone, the news you are giving them will devastate them. It’s a moment they will never forget.

And sometimes it’s a moment you never forget either.

Years ago I was working in a busy emergency department when sometime mid-morning, an ambulance brought in a middle aged man in cardiac arrest. Someone had found him unresponsive in his parked car and called 911. Paramedics had intubated him at the scene, begun CPR, and brought him to us. We did what we could, but unfortunately, there really wasn’t much for us to do. In spite of everyone’s best efforts, the patient was dead on arrival.

After the death pronouncement, I signed some papers and got cleaned up and headed to the “family room” where the patient’s family was waiting for me.

Two middle aged women were in the room when I arrived—the patient’s wife, and a friend of hers.

I introduced myself, and as I began asking what they knew about what happened, I noticed the wife had an open Bible on her lap. She had been reading just before I arrived.

The women told me that they only knew that the patient had been sick. He had phoned his wife from his car when he got to work saying he didn’t feel well, and then a few minutes later she received a call from his work that he had been taken to the hospital. She had last spoken to her husband maybe 45 minutes before. In other words, she, and her friend, had no idea what had happened, and they were expecting a perfunctory update about his health, not the devastating news I was about to deliver.

I took over the narrative when the wife finished her side of the story, just as I had taught the medical students to do. I slowly and deliberately explained to the wife that someone had found her husband in his car unresponsive, probably a few minutes after he had called her. I told her that when the paramedics arrived her husband’s heart was stopped and he was not breathing. I told her that he had been intubated at the scene by the paramedics and brought to us in full cardiac arrest. I told her that we did everything we could, but unfortunately it had not been successful, and that I was very sorry to have to tell her that her husband had not survived the incident. He was dead.

When I finished speaking, the friend gasped and turned towards the wife, placing her hand tenderly on the woman’s arm.

They both stared at me in disbelief.

They were completely stunned. Only a few minutes before, this wife had been speaking with her husband on the phone, and she thought he had been transported to the hospital because he wasn’t feeling well. She had absolutely no idea this had happened. She was not expecting this at all.

But her response was something I was not expecting.

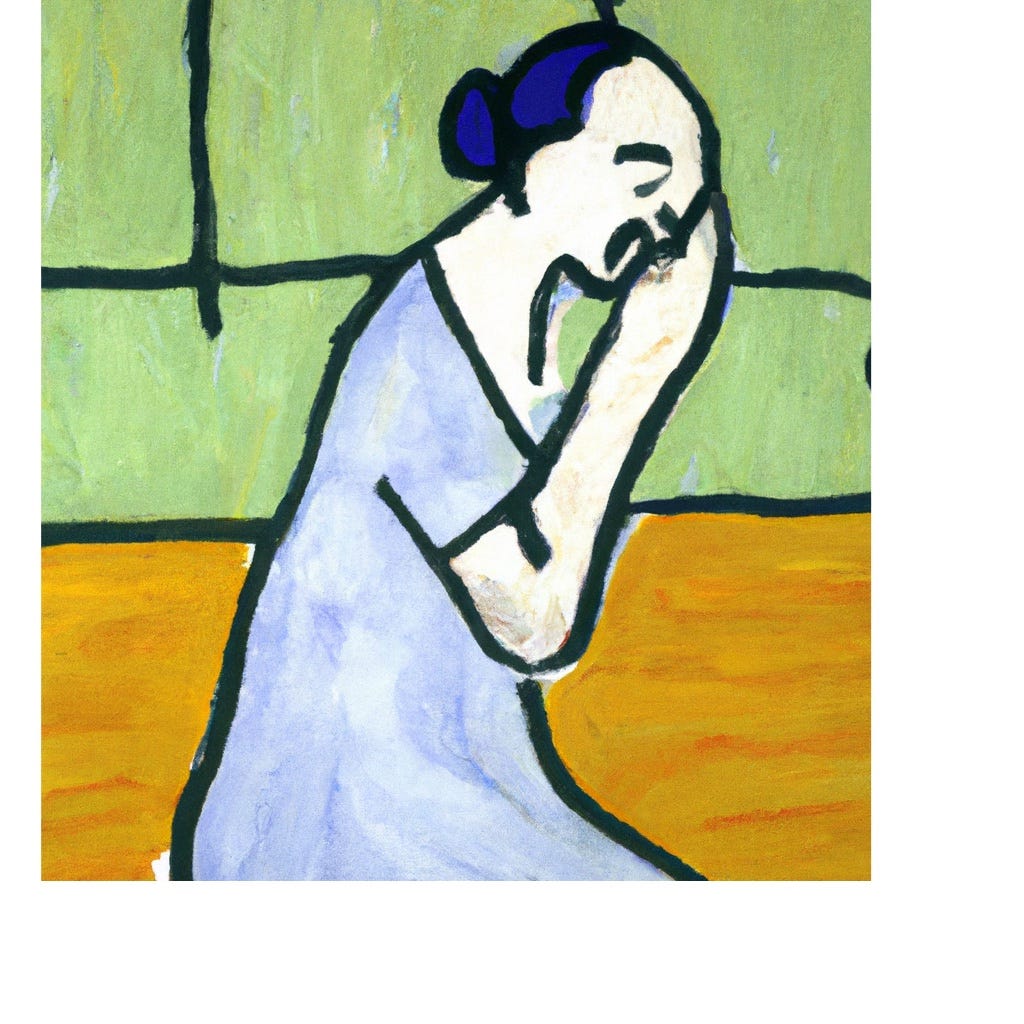

After a long pause, this woman turned her gaze from me without a word, without a cry, closed her eyes, and lifted her face and hands toward heaven in silent prayer.

It was a singularly powerful moment, a reflexive response done without pretense.

A raw, unrehearsed response that was powerful and beautiful and moving.

In her moment of deep grief and anguish, the facade had dropped and what was real and true was exposed.

The toothpaste was out of the tube, and what it showed was glory.

Dr. Bledsoe, I really enjoyed reading this article. I worked at Baptist for 15 years and saw a lot. I was the Information Associate for Labor and Delivery at Baptist Springhill. I know it was encouraging to you to see this precious lady's response at such bad news. You are so right; what's in the toothpaste will come out when squeezed. God bless you in all you do. Keep sharing.